Last week, I presented a conversation I’d had with ChatGPT on the subject of Grace and Salvation. Jason commented on the importance of carefully crafting the questions or “prompts” you give to ChatGPT and similar AI “models”. The quality of the response you get is directly related to the quality of your prompt. Remember the GIGO principle—Garbage In, Garbage Out.

Some of you still seemed still a bit leery about the value or role of AI in things of the spirit, but most of you seemed in general to agree that people are going to find themselves talking to an AI at some point (resistance is futile!) so I was asked to expand upon this very important topic.

In carrying out my assignment, I was reminded that the art of questioning is hardly new. We’ve been refining it throughout history. This thought led me to explore its use in religion, and that exploration led me to a Jewish scriptural commentary that seems to me to be a pinnacle of the art of questioning. And that, finally led me to wonder whether other religions and sects and denominations—such as, for example, the Seventh-Day Adventist Church—are questioning enough.

AI Prompting

In AI models such as ChatGPT and Claude, a “prompt” is a question that you ask of it, or an instruction that you give to it. You might instruct it to “List the Ten Commandments” or you might ask it: “What are the Ten Commandments?” They amount to the same prompt. Either way, you are prompting it to search through its database and tell you something you want to know.

To be effective, a prompt needs at least three basic attributes: It should be (1) clear, (2) specific, and provide (3) context so that the AI model understands the task accurately and can produce a valid and reliable response.

Clarity, specificity, and context all help reducethe chances of misinterpretation and enhance the reliability and relevance of the generated responses.

In preparing this talk, I gave several prompts to ChatGPT. Here is one of them:

“Act as if you were a human looking for help in understanding things of the spirit. Give me three examples of prompts you might put to an AI such as ChatGPT.”

I hope I was clear, and I certainly gave it a context (understanding things of the spirit), and a specific request for examples. But notice that I added a fourth element to the prompt: a role (to act as if it were a human looking for help).

Here is the response it gave:

Here are three examples of prompts I might put to an AI like ChatGPT as a human looking for help in understanding things of the spirit:

Prompt 1: “Can you help me understand the concept of spirituality and how it relates to my daily life? I’m looking for a deeper connection with something greater than myself, but I’m not sure where to start. Can you provide some insights or guidance on how to cultivate spirituality in my daily life?”

Prompt 2: “I’ve been struggling with feelings of guilt and shame, and I’m not sure how to overcome them. Can you offer some spiritual guidance on how to let go of these feelings and find forgiveness? I’m looking for a more compassionate and loving approach to myself and others.”

Prompt 3: “I’m interested in exploring the connection between spirituality and social justice. Can you provide some insights on how the Holy Spirit inspires us to act for social justice, and how we can deepen our relationship with the Holy Spirit through acts of love and justice? I’m looking for a more nuanced understanding of how my faith can inform my actions in the world.”

These prompts are designed to elicit helpful and informative responses from ChatGPT, and to provide a starting point for further exploration and reflection on spiritual matters.

These three prompts—which are the work of ChatGPT itself, remember—are examples of how prompt engineering can be applied to guide AI models like ChatGPT to produce specific and useful responses. Again, note that the guiding elements included the role the AI was meant to assume, a specific instruction or task, open-ended questions, and some context to the prompt.

All three prompts assume the role of a curious individual seeking to understand spirituality. It is not always necessary to include a role in a prompt, but in this case I found I had to tell it to assume the role of “a human interested in things of the spirit” in order to get it to give me these sample prompts. When I first gave it the same prompt but neglected to give it a role, it assumed I was myself looking for actual spiritual guidance rather than looking for the AI’s advice on how to engineer prompts that would result in good spiritual guidance. So you often have to play around with prompts to get what you want.

Let’s analyze the prompts ChatGPT gave me:

Prompt 1 asks specifically for a personal definition of spirituality, contains three open-ended questions, and provides “spirituality” as the general context.

Prompt 2 asks specifically for spiritual guidance on overcoming guilt, contains implicit questions about how to overcome negative emotions, and provides a context of struggle with guilt and shame.

Prompt 3 asks specifically for insights on the Holy Spirit, contains two open-ended questions,and provides a context of social justice.

In the jargon of AI developers, these prompts were “engineered” so as to guide the AI to produce useful, specific, and high-quality responses.

But given the early stage of development of today’s AI models, we still need to understand their limitations and learn how to communicate with them effectively. It is amazing enough that AI manages the imprecision and ambiguity of natural language as well as it does already, but it does have limits, so go for clarity and try to avoid imprecision and ambiguity!

Asking Questions

We may conclude from the foregoing that AI can be an indispensable tool for solving complex problems and driving meaningful progress in a culture that values the art of asking profound questions and crafting the right prompts.

It seems the American education system has got that message, after some initial panic that ChatGPT would just let kids cheat on doing their homework. The very thing one New York City Dept. of Education spokesperson went on record as fearing—that AI would not build critical-thinking and problem-solving skills—was flat-out wrong. Bloom’s Taxonomy, which Jason has taught us about in class, puts critical-thinking and problem-solving skills above the basic educational skills that traditional education has tended to focus on, and it is precisely critical-thinking and problem-solving skills that AI models help us develop.

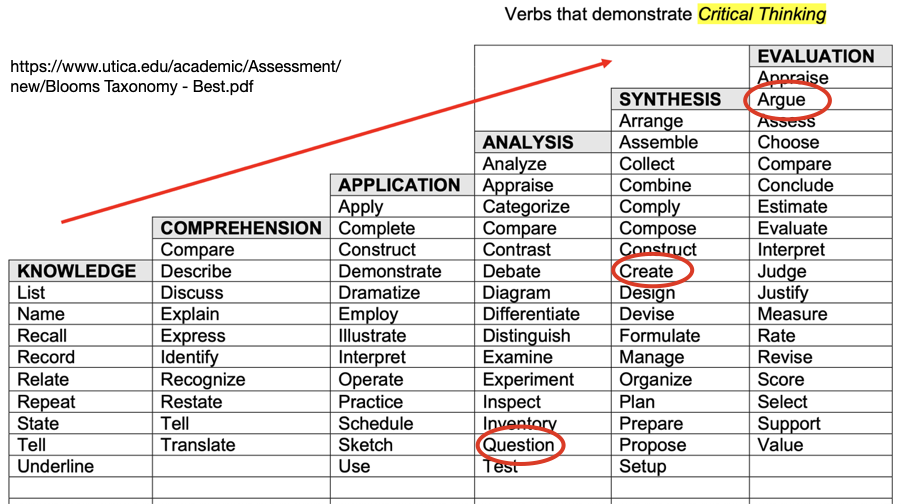

The chart below, from Utica University, breaks down “critical thinking” into the top three tiers of Bloom’s hierarchy: Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation. Note that questioning and arguing are part of critical thinking—and critical thinking is precisely what AI prompting makes us engage in, especially knowing its limitations (such as its propensity to hallucinate.) In “old school,” students are expected “to write and perform like robots,” as an Ol’ Miss professor put it.

Culture and Questions

If prompting is questioning (and it is), then it’s hardly new to us. Throughout history, questions have been key to understanding ourselves and the world around us. Questioning is central to science, but it also has been associated, in research studies, with individual confidence and emotional intelligence (the extent to which you can control your emotions to relieve stress, empathize with others, and defuse conflict).

Asking questions is natural. (It is actually more natural for women than for men, research has found. Think about the husband and wife getting lost while driving, and about which of them finally rolls down a window to ask a local for directions. 😉 ) Kids start asking questions as soon as they can form words, but in adulthood, questioning tends to drop off—unless you’re Socrates, or a scientist, or just a person who wants some serious answers to some serious questions. For them, questioning is an art. It takes practice, commitment, and an environment supportive of inquisitive behavior to learn to form, and then ask, good questions.

Questioning of course has long been used in education. Socrates asked questions of people in order to teach them—the Socratic Method, as it is well known. So did Jesus, as Dr. Weaver has noted in a previous class. But questioning can also be discouraged. “Pestering” questions can be counter-productive, as most children soon learn; but parental dictatorship is nothing compared to the discouragement of questioning by dictatorial governments, societies, cultures,… and some religions or branches thereof.

They discourage questions through censorship. They restrict access to information and forbid topics or viewpoints that might threaten their ideas and ideals. They punish critical questioning of their own viewpoints, in order to suppress dissent and enforce conformity. They also employ stereotyping and bias in their messaging and policies to marginalize and/or stigmatize groups or ideas they feel may threaten them or their ideas.

Liberal, progressive, or democratic governments, societies, and religions, in contrast, encourage questioning, and they do so in three ways:

First, they encourage questioning through education systems which, in contrast to indoctrination systems, emphasize critical thinking.

Second, they encourage questioning through policies that protect freedom of speech and expression.

And third, they encourage questioning through a free and independent press that (if not hijacked by bad actors, and that’s a growing IF) enables informed decision-making by providing access to diverse perspectives and information.

Not every culture values the art of questioning. Dictators only value the art of leading questions, which essentially predetermine the answers. In some West Papuan cultures, according to ChatGPT, to question can be taken as a sign of mistrust. This odd fact (assuming that ChatGPT was not lying, or “hallucinating” as it is called) prompted me to prompt ChatGPT to tell me about the opposite end of that spectrum.

And lo and behold: There—directly opposed to a culture that stifles questions—stands the Talmud, a central text of Judaism, comprising a vast collection of Jewish oral traditions, discussions, and debates that were compiled over six centuries. It covers topics from Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, and history, to biblical interpretation.

A Haven for Intellectual Inquiry and Doubt

The Talmud was founded in 70CE, after the destruction of the Second Temple (Israel’s “nakba”, so to speak), by—of all people!—the Pharisees, who in seeking to impose strict adherence to the law were evidently prepared to countenance significant questioning of it.

It is a record of the discussions and debates of groups of rabbis who lived in the “Land of Israel” and in Babylon between the time of Christ and the 6th century CE. It presents conflicting perspectives on the topics it covers. It is an approach that acknowledges that truth is complex and that a single perspective or interpretation may not fully capture or represent the essence of that truth or concept or issue.

The debates are not aimed at resolving the contradictions or reaching a consensus, but rather at exploring the complexities and nuances of the issues. It is designed to encourage critical thinking, analysis, and intellectual rigor. I haven’t read it, but on the basis of ChatGPT’s description of it, it seems to me that the Talmud may be the quintessential Book of Questions.

The significance of contradictions in the Talmud lies in their revelatory power—their power to enlighten, even knowing that truth is not always straightforward or absolute, and that different interpretations can coexist and be valid. Hence the importance of study, debate, and intellectual inquiry in the pursuit of understanding and wisdom. I personally believe that this very class of ours operates along the same principle, and that is why we find it so enlightening.

Talmudic scholars today continue to interpret the Talmud through dialectical debate based on principles of “sacred intellectualism,” which combines profound faith with questioning skepticism and an incessant self-criticism. “Sacred intellectualism” is, again, something we seem to be practicing in this class.

The “profound faith” of the Talmudic scholars includes the first principle/premise that every word of the Talmud was precisely weighed and measured, is of divine origin, and hence even the most far-reaching conclusions may be drawn from them. A second premise is that there is a common, shared basis to be found through discussion of its words.

Talmudic scholars’ emphasize the importance of understanding not only the context and nuances of the issues but also the lives and personalities of the Talmudic scholars themselves, as these can provide valuable insights into the meaning and application of their words.

In summary, Talmudic scholars interpret the Talmud through a rigorous and nuanced methodology characterized by a deep respect for the text, a commitment to understanding its nuances, and a willingness to engage in dialectical debate. This methodology is rooted in the principles of sacred intellectualism and an emphasis on finding common ground, resolving contradictions, and uncovering deeper meanings of the text. And again, to me, this reminds me very much of our class.

Religious Education

Which brings me to my final point: Religions and their sects are essentially schools. Their purpose is to educate people about things of the spirit. Personally, I have my reservations about whether we need any such schooling at all. Perhaps many people do, since religion appeals to so many, but I’m not sure it is strictly necessary to turn to a priest for spiritual guidance when we can turn directly to God inside of us. It might even be dangerous to do otherwise. What if the middleman’s guidance conflicts with God’s guidance?

However, acknowledging that religion appeals to many, do religions make good schools, good educators? Aren’t many religions or sects stuck at Levels 1 and 2 of Bloom’s taxonomy—Knowledge and comprehension? That is, are they mainly concerned with indoctrinating their students (their congregations) to remember information supplied by the sect and forcing them to comprehend that knowledge in conformity with the sect’s interpretation of it?

Conclusion

We’ve come full circle from describing the mechanics of prompt engineering, though a general discussion of the art of questioning, then a specific description of a religious group that practiced that art in a most powerful manner, to the issue of whether other religions even tolerate the idea of prompting outside their own box.

Does your religion provide an environment supportive of inquisitive behavior? Does it encourage and help you to learn to form, and then ask, good questions?

Do you personally know of a situation where asking the right question or giving a clear prompt made a difference?

Do you believe there are limitations to the types of questions AI should be asked, especially in matters of spirituality and personal guidance?

How might questions and answers on spiritual matters differ between ChatGPT, an ultra-orthodox rabbi, a Trappist nun, a Jehovah’s Witness, and… (ducking!)… an SDA Church elder?

If an AI model becomes the most used source of information, what happens to the debate and discourse that seems essential to reaching spiritual enlightenment? Or is debate not essential? Or will different AI models start to debate one another?

Jay: What is the difference between a question and an answer? In the realm of AI, and also just in talking to people, the type of question you ask—their specificity, context, and clarity—are so very important. In the field of education, the type of question ascends through Bloom’s Taxonomy. We can ask questions about the same topic in different ways, such as a knowledge-level question, a comprehension-level question, a synthesis question, or an evaluation question.

The idea of questioning and its complexity, and our tolerance for it, in my opinion have a significant impact on our spirituality. Our tolerance for questions seems lesser in a religious (as opposed to spiritual) context, which puts a formalized and organized wrapper around spiritual matters, and greater in a purely spiritual (as opposed to religious) context, which tends to be more global, universal, and timeless.

In a religious context, when we talk about things of the Spirit, we are often looking for answers and are not too interested in questions. We also tend to be highly focused on the right answers—what are the right and wrong answers to questions. It’s a drastic difference.

It’s very interesting that our society may be progressing more towards wanting to be a society that gets answers rather than one that just wants to ask questions. I think that’s the same rub with AI as it is between religious organizations: People are afraid that the answers they get may be different from the answers they want. Or they may fear that the answers (from AI, and from religion) will be founded on erroneous thinking. That’s the problem when we focus on answers rather than on questions: those fears become stumbling blocks in our thought processes and in our brains as we think about spirituality.

It’s becoming more and more apparent to me, through our class discussions, that the answers are not nearly as important as the questions we ask. Likewise, with the questions raised in class by other people: the questions are more important than the answers because the questions develop our understanding of the Spirit and our perspective on the spirit.

C-J: I think the beauty of humanity lies in that discourse. As history progresses, those questions will be formulated differently in the context of time and place. When the question was, “Have you or do you have this operational in your life?” I see it in counseling and as an educator, and they are essential and always evolving. I agree with you, 100%.

And I don’t like to say that, but I’m 100% sure that a well-formulated question goes beyond a prompt. A prompt still has boundaries, whereas a question evolves into the discussion and, depending on who’s present, I can teach the same lesson to a different class, but my sense of who my audience is changes what I’m doing and how I’m doing it with that group of individuals. Because what they’re looking for through their questions is an indicator of what and how I will teach that lesson or set up that lesson.

Really good teachers know the art of discovery has more power than my words alone—they’ll forget my words. But if they are part of the process of discovery, it takes root, and they will have their own questions when they leave my presence, and hopefully, I will give them an opportunity to learn how to be lifelong learners.

This certainly applies to the spiritual realm because I believe it is my spirit that motivates me every day, not just my curiosity, but my curiosity is rooted in my spiritual relationship with my Creator and my community, people I brush up against, who are my teachers and my mentors and guides throughout my life. I believe they are all intentional and part of the purpose of my time here, with God orchestrating this wonderful event we call life.

Donald: Everything’s done in the context of one’s own insights in space and time, but as time progresses, it seems that all of society is more interested in stopping at Bloom’s application level and not moving on to the analysis level.

When I go to get my news, I want the facts. I want the information told to me. And that’s the frustration, I think, where we find ourselves these days, depending on the source of our news which doesn’t allow for more questions. It’s saying, “This is the way, these are the facts.” It’s not encouraging me to go beyond that.

So I think it extends beyond the church or religion. I think it extends into all of society right now, in terms of why we’re so divided. “I don’t agree with you, and that’s the end of it,” or “I agree with you, please be on my team,” kind of thing. So, we are actually moving toward AI, and it’d be interesting to look at this and go, “Okay, if we looked at news sources 20 years ago, did they provide a foundation of knowledge in order to move toward analysis?” But I believe now the knowledge isn’t asking us to analyze anything; it’s just wanting to provide the nutrients for me to support what is being fed to me.

That’s number one. I’m thinking about those of us that are Adventist, and when we were kids, we had Sabbath school lessons where the prompts were basically the Sabbath School lesson, you have two or three lines, and then you did the answers that needed two or three lines. So the whole idea of moving through the discussion was well defined by church literature.

I’m not saying they did that to control us; it was maybe a way to get us to move forward. But that’s one reason I was attracted to this class, probably 40 years ago, because all of a sudden, I went into a class that wasn’t asking the questions right out of the Sabbath School lesson. Think about that, in terms of the mission story, everything was pretty tight in terms of what was being fed to us.

Another point is the source of knowledge. That’s really important. You can have a continuation upwards toward critical thinking, but if you put bad information in, you get bad information out. So who provides the source of my knowledge now? And that goes back to my question about news sources.

This one’s going to be a little bit controversial, but I think it’s true: Who asks a question is more important than the question itself. If I’m sitting in a room with other educators, and someone who is highly respected asks a question, then all of a sudden, the importance of the question rises. But if you’re way down here on the food chain, your questions aren’t that important, your prompts aren’t that important.

And lastly, my role in asking questions has been very important over a 40 year career in Adventist education. I’m not sure at what point parents wanted me to move students beyond Bloom’s application level. I sensed that some sent their kids off to college not to explore ideas, but to toe the company line. Since my paycheck came from the corporate church, my role is inevitably somewhat constrained.

C-J: I think that crisis is probably the greatest motivator for change. Going back to the Pharisee, saying, “Oops, we need to take a look at this,” after a certain period of chaos, an extended period within the church, within politics, the region, etc. So, crisis, to me, is really critical. As an individual, I’ve had many periods that I would identify as a crisis, where I came to a place where I needed to ask those internal questions. Education does the same thing. In the foundation of youth, we want them to receive a consistent message and application: “You’re going to learn this today because you are going to use it tomorrow when we do this project.” Or the goal for me is to get you from second grade to third grade, and you must have these skill sets before I can, in good conscience, tell you you’re ready.

As an adult, unless we’re in a situation like Donald—to be the company person—what we say out of our mouths supports our employer, our identity, and our reason for being in that position, in that job. When we become independent, choose our life partners, choose our friends, when we are more flexible and less tied to finances, we are more fluid in allowing ourselves to be with people considered ‘other.’ We want to learn—“Tell me about who you are, tell me about your beliefs, tell me about where you came from,” and have that exchange.

I do believe there is a real problem with how we get our news. Everything from financial news to political health is limited to digital bytes of information, fit within a timeline. I don’t even watch TV for my news; I just do news feeds and go, “Dang, no, this is interesting.” And I might go off and try to find more information about a topic so that when I’m reading it, I can insert knowledge simultaneously that I’ve gathered to weigh it. But in real life, we all get 24 hours per day, and I think it’s really hard at the speed of light that we are losing our grasp of community, and that’s why our youth are struggling in terms of mental health, and adults too. How can I put food on the table, buy a home, have a personal life, have any relationship when it’s all based on content? In that spirit, we are spirit beings.

I met a girl the other day, she took a 90-credit hour course to be a peer counselor working with veterans. She’s very young, she’s had some trauma in her life. And I said to her, “So, did you go to our institute to get this course? Because the last time I knew it was being offered there. And where did you do your practicum? How long was your practicum? And when will you be taking your exam?” She said the whole thing was online. And of course, she would be taking her tests, I said she had no practicum. She said, “No, everything in my head just said walk away.” And yet this person was going to be in a position where she would be peer counseling other veterans, young and old. The experiences are different. Her life, she’s still doing her own war story. And a good counselor has moved past that.

I use that as an analogy when it comes to examining our spiritual life. I’m still, like Paul made the analogy, “You’re not children anymore. You’re not nursing anymore. You need meat.” And meat requires risk-taking, responsibility, and accountability. Youth are in that process of growing up. I don’t know who hired her, but it was a mistake. And I doubt that she’ll be there very long.

My mentors are usually five, seven, ten years older than me. But as I’ve aged, I find myself as the mentor. And I say to myself, “If I were this person, what does this person not know about him or herself? What does this person need to know, in order to get to the next level that I hear them saying, by their questions, ‘I don’t know how to do this.’ That takes a lot of skill sets and experience.”

To me, the art of storytelling is very critical in using imagery, because people really don’t remember literal words, but they remember images, and how it made him or her feel. And to me, we don’t have that context when we’re working with a device. I get knowledge, but I don’t get the visceral imagery. I have to be mature in order to draw parallels in my experience. And I think our children are suffering traumatically—I mean network trauma, there’s this big hole that is just not getting taken care of. It doesn’t really have a boundary.

Reinhard: If AI produces Scriptural information, then 2 Timothy 3:16-17 still applies. It says:

All Scripture is inspired by God and beneficial for teaching, for rebuke, for correction, for training in righteousness; so that the man or woman of God may be fully capable, equipped for every good work.

While it is good that AI can answer even difficult questions, it’s still a machine lacking moral standards and a spiritual life connected to God through the Holy Spirit. But God may be speaking through the machine to people who don’t have any other means to know God. Maybe God provided this means to them, and maybe they can come to know God in that way.

Christians already know how to respond to God’s calling and we have a dynamic relationship with Him. In our spiritual life, we seek the truth, we want to explore questions that we don’t have answers to. In this class, we always deal with open-ended questions, which helps us to grow our relationship with God and one another. If this is beneficial for us, then it is our duty as Christians to share with our families and the people with whom we come into contact.

Our discussions are lively and good, and if they are not against God, then they are for God! Is AI going to promote and advance God’s work, without violating God’s moral law? I don’t think so. AI is good for people who’ve never come to know God through organized religion. And as technology advances, more and more people will have the opportunity to be saved.

I read a poll the other day that said 30% of respondents consider that salvation is not through Jesus, and only 70% said they are going to be saved through Jesus. Of course, the salvation of the 30% is still in God’s power: if they are doing good, God will consider them, as we know from Romans 2. They may have their own law, without the gospel, but God will hold them accountable.

We want to know the truth; we want to know more about God; and in our daily life, as well as in our spiritual life, we want to be close to God. I hope AI may help us to get closer to God and lead a better spiritual life. In the end, we’re going to receive the fruit that we’ve been cultivating.

Michael: How could an answering machine have a grasp on spiritual matters? AI is designed to be an answering machine. If we agree that spiritual matters need to be questioned, how can we do that in a meaningful way—not just asking questions to get easy, pat answers, but asking questions that may be confusing, confounding, and may not even be answerable?

David: That’s the point of AI prompting. In creating this talk, I gave ChatGPT many prompts. I didn’t just give it the topic and tell it to write my talk for me. I asked it a bunch of different questions, and through its answers, I became more enlightened through being led to ask better or deeper questions. I could have gone on forever, but you have to stop somewhere, and I ended up with the questions I ended my talk with. I really wasn’t expecting the machine to give me final answers. I don’t think the answers are to be found in the machine—they are to be found in the human questions, as Jason has said.

I think Reinhard is absolutely right that what we’re after is personal spiritual development. Donald’s concern about the differentiation between corporate indoctrination versus individual spiritual education seems justified to me. Indoctrination is fine for a corporate environment, for teaching people to live and work and achieve goals within a given corporate environment and its rules. The first three levels of Bloom’s taxonomy are okay for indoctrination, but they will not do for the critical thinking essential, in my view, for true spiritual development.

ChatGPT doesn’t give final answers to existential or spiritual questions. It just leads to more, but deeper, questions. I’m beginning to be able to differentiate issues a little better than I could before. It is leading me towards enlightenment, but it will never give me total enlightenment.

Michael: I don’t see how that has to be specific to ChatGPT. I could ask questions via other sources.

David: That’s true. ChatGPT is just another medium for asking questions. The Jews have the great medium of Talmud debates. We do something similar through the medium of this class. There are many, many ways of doing it, but ChatGPT makes the process more productive. You can do it quicker, you can get to deeper, richer questions much faster.

Carolyn: Many times, I ask spiritual questions within the confines of religion, but ChatGPT provides non-judgmental answers. As growing Christians, we have questions but sometimes we’re reluctant to ask them because they may affect our credibility, our reputation, and our standing among our fellow churchgoers. They may think less of us if we ask questions that are not at the same Bloom’s taxonomy level as their questions, or the level we are expected to be at as “Christians in workshoes.”

David: Carolyn has nicely illustrated the difference between asking ChatGPT and asking a Trappist nun a question. You’ll get a relatively non-biased answer from ChatGPT. Will you get a non-biased answer from a Trappist nun, or from a Seventh Day Adventist elder? These are people who, to some extent, have been indoctrinated with a point of view.

There is certainly a great danger (and some people are very worried about it) that AI will be indoctrinated by humans, rather than just given a universal education, but right now I don’t think we’re at that stage.

Donald: I think this goes back to my probably poorly worded point about considering who asked the question. Do I need to listen, or don’t I need to listen, based on my respect for the person who’s asking the question?

I’m not sure that I always want an unbiased answer. Sometimes I’m okay with a biased answer. If I go to two different Adventist churches in this community, I may get different answers. But that’s okay; it builds my database. So it’s okay to have a bias, as long as I understand that it is a bias.

But where I think we start arguing is about facts in making a decision about something that’s important. Because some people describe their biased answer as a fact. Maybe I do, too. I think that’s a real problem—that people describe their perspective as facts. It’s perfectly fine for you to have an opinion, for me to have an opinion. But to state an opinion as fact is a totally different issue.

Don: We’ve talked many times in this class about questions, and about the fact that the Bible is a book of questions as much as it is a book of answers. We’ve noted that questions are timeless in many ways, and are therefore the method that God and Jesus both used explicitly in the Bible.

We want so much to have solid answers and to be on some kind of truth footing. Because for some reason, we have the notion that if we believe the right thing, we’re going to make it into heaven. If we don’t believe the right thing, somehow that’s a prescription for not making it into heaven. But the lengthy discussion that we’ve had about grace puts to rest the issue of what the answer is. The answer is not facts. My facts are different from your facts. The answer is a person. It is the saving grace of Jesus Christ. That makes information and answers and facts unimportant. If we’re saved by grace, then whatever facts you cling to as being your facts and your truth are fine. But they are not what your salvation depends upon.

And so I think we have to look for other reasons. I think there are reasons to understand and to share and debate facts and ideas and answers and to use the Talmudic principles of trying to understand what we can know about God. But in the end, we have to recognize that that’s not what saves us. What saves us is our faith in God’s grace, and that, I think, lays the whole issue of facts and questions to rest, at least in my opinion.

We will pick this discussion up next week.

* * *

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.